Why the Latest Nobel Prize Winner Makes Perfect Sense

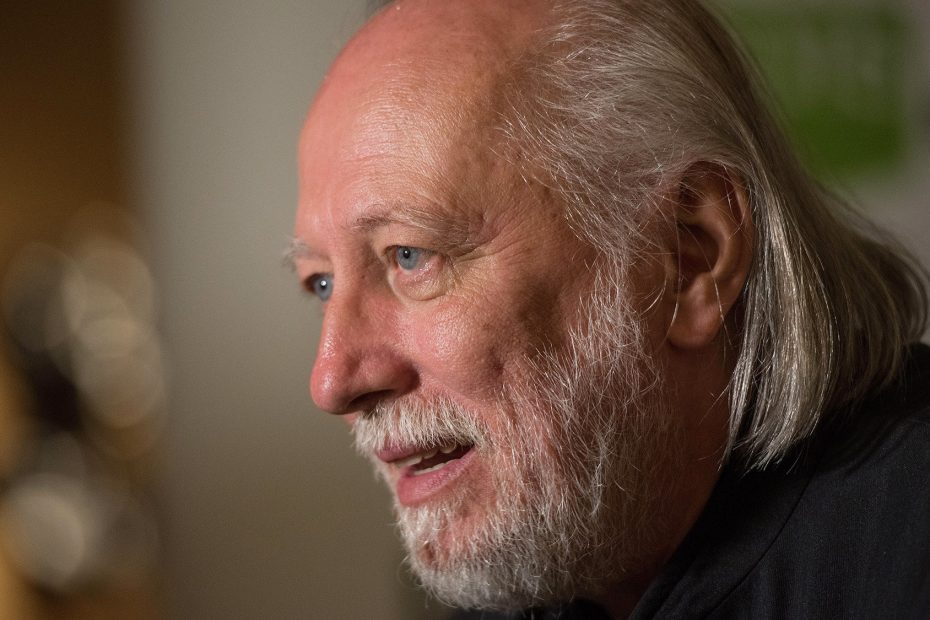

László Krasznahorkai, who won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature today, is not the easiest writer to read. His sentences can go on for hundreds of pages; his plots don’t resolve, they dissolve; and his persistent mood is existential dread. But the Hungarian novelist’s central theme is easily parsed and sadly evergreen. Krasznahorkai writes about the stultifying effects of political oppression, but he also writes in defiance of people’s readiness to accept them.