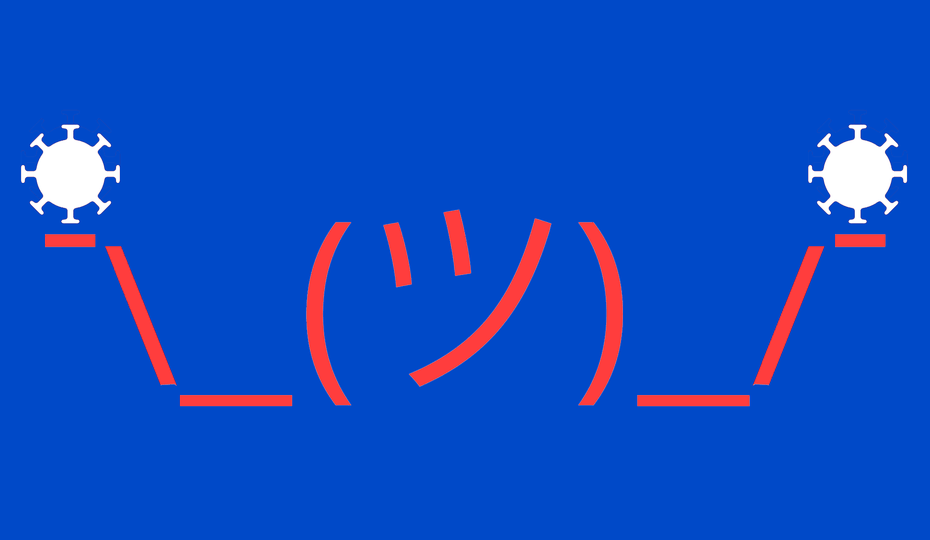

Of Course Biden Has COVID

And there it is: President Joe Biden has tested positive for the coronavirus, the White House announced Thursday morning, and is dosing up with Paxlovid to keep his so-far “very mild symptoms” from turning severe.In some ways, this is one of the cases the entire world has been waiting for—not sadistically, necessarily, but simply because, like so many other infections as of late, it has felt inevitable.